Ali* grew up in Mombasa, the coastal paradise known for its sandy beaches, swaying palm trees, and warm sunshine. For most, the city represents an escape but for Ali, a young gay man of Arabic descent, this paradise holds a darker reality. At just 25, he has endured abuse from his male relatives, who tried to force him into what they believed was “normal.” Behind Mombasa’s vibrant culture and serene beaches, a silent struggle persists for locals like Ali, who face the constant fear of being outed and subjected to harmful “conversion therapy” simply for being themselves.

“Conversion therapy” is defined as attempts to change a non-heterosexual person to become heterosexual, according to the Oxford Dictionary. These attempts to change an individual’s sexual orientation or gender identity include harmful methods such as coercion, threats, forced marriages, detention, prayer rituals aimed at “curing” homosexuality, and even acts like “corrective” rape, according to the Shame is Not a Cure report by galck+.

Ali lost his mother in 2010 when he was just 11 years old. His father remarried, and Ali was raised by his stepmother. As he reached puberty, Ali began questioning his sexual orientation but kept his feelings hidden until he turned 18. When he finally came out, his desire for acceptance was met with violence.

“I went to my stepmother first and came out to her directly, telling her I’m gay. I hoped she would handle it better because my father, being a strict and religious Arab man, made it difficult to be open. She promised to talk to him, but he would hear none of it. My family ended up beating and harassing me, and I had no voice in the family. When I was younger they locked me up in a room and at one point, they even chased me away,” Ali recalls.

Despite being the fifth of seven children, Ali was completely isolated and lonely as all his siblings turned against him. His older brothers and father were violent, accusing him of “sinning”. This kind of reaction is common, according to Swabra Mumba, a psychologist in Mombasa County. Families often believe they act out of love to protect their reputation, shield their kin from stigma, or “save” them from sin.

“Parents often believe that being LGBTQI+ is sinful, and see conversion therapy as a way to “save” their loved ones,” notes Mumba. “Religious teachings can reinforce this, framing it as a moral duty to guide family members toward a “righteous” life. In cultures where family honour is paramount, having an LGBTQI+ child is seen as shameful, and “conversion therapy” is viewed as a way to “correct” this. Some parents, fearing discrimination or violence against their child, may turn to conversion therapy in a misguided attempt to protect them.”

These harmful practices are often fueled by misinformation about the LGBTQI+ community and the law. Given that same-sex relations are illegal under Kenya’s penal code, many people believe they cannot report the perpetrators. However, Michael Kioko, an advocate with the Centre for Minority Rights and Strategic Litigation, firmly disagrees, highlighting that survivors have constitutional rights they can invoke to seek legal recourse.

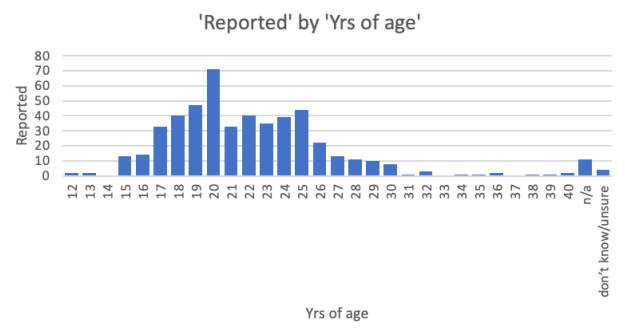

Findings published in the Shame is Not a Cure report by galck+ reveal that minors as young as 12 are subjected to “conversion therapy.” While they have the same rights as adults, Kioko acknowledges that achieving justice for minors is challenging.

“Minors deserve protection from manipulation, as they have the same rights as adults. However, in Kenya and Africa, advocating for LGBTQI+ rights often leads to misconceptions that one is a recruiter of minors [into the ‘practice’].. We must navigate this carefully, especially since minors may not be adequately protected. Intervening becomes difficult when they are expelled from school for being perceived as queer, and returning home can lead to further rejection.”

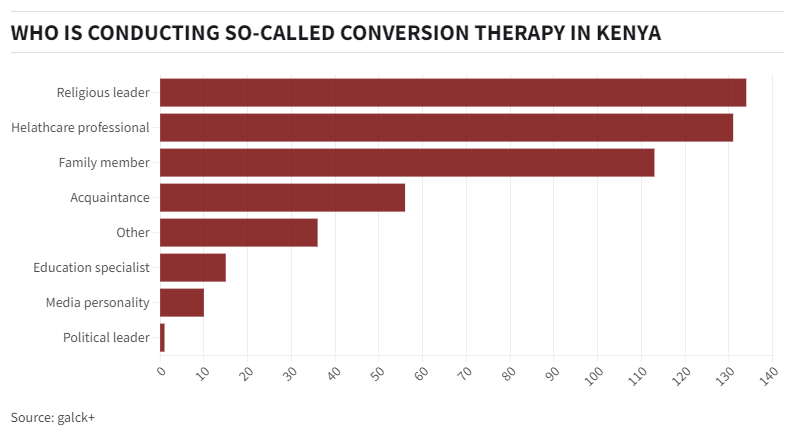

Alarmingly, healthcare professionals are often implicated in administering conversion therapy. Mumba urges caution when consulting psychologists, as some may misuse their expertise to cause harm.

“Some therapists try to change someone’s sexual orientation by challenging their thoughts, especially with cognitive behavioural therapy. Others use outdated psychoanalysis, claiming identity issues stem from childhood trauma. Worse, some use aversion therapy, like electric shocks or nausea drugs, to make people associate their sexual identity with something negative,” Mumba explains. “They use unpleasant stimuli, like electric shocks, while making the person focus on negative thoughts about the LGBTQI+ community. The goal is to force a negative association with their sexual identity.”

Ali endured abuse from 2017 to the point of needing medical attention, yet he remained at home due to his dependence on his family. When the abuse failed to change him, his family forced him into marriage to protect their reputation.

“My father wanted me to marry a woman,” Ali recalls. “Eventually, they arranged my engagement, and I went along with it. I thought about running away, but I couldn’t support myself financially. So, I got married against my will.”

After his wedding and everything he had endured, Ali finally reached his breaking point and ran away from home, seeking refuge in a mosque. Instead of finding solace, he was publicly humiliated.

“I attempted to run away and sought refuge in a mosque, thinking I might find safety there. However, my father, being a respected leader in the Islamic community, found out and came with other leaders to force me out. During congregational prayers, in front of many people, I was humiliated and chased away. In our community, being gay is completely unacceptable, and some may even suggest death for bringing such ‘disgrace’.” The incident was so traumatising that he does not attend prayers in that mosque anymore.

After leaving the mosque, Ali stayed with a friend as he tried to process his situation. His friend offered shelter but insisted Ali should not let anyone know he was helping him. The support came with the underlying fear of being associated with someone who is LGBTQI+. Realising he couldn’t rely on his friend’s charity forever, Ali returned to work at his father’s mini-supermarket, where he was in charge of sales. However, his professional life became challenging as colleagues discovered he was gay.

“I got a job, but when colleagues learned about my situation, I faced stigma and hate speech. It became unbearable, so I left after three months. This affected my social life; I stopped interacting with others.” Ali recalls.

This reaction is common among those who have undergone “conversion therapy”. According to Mumba, “Many survivors experience strained family relationships, feelings of betrayal, and resentment. They often withdraw from social circles due to shame and trauma, fearing judgment and rejection.”

Ali eventually mustered the courage to open up to his wife, only to discover she had already suspected. While opening up created a safer environment in his matrimonial home, he continues to stay married out of fear of stigma and possible attacks if he were to live openly as a gay man.

Ali’s story is not unique. Mumba recounts a chilling case from one of her patients: “I have a client whose family invited men to rape her because she came out as a lesbian. Her father believed he needed to “show her” she was a woman, subjecting her to horrific abuse that she endured in silence for years until she found someone she could confide in.”

Mumba points out that such crimes have harmful psychological effects on survivors.

“Survivors often face mental health issues like chronic depression due to shame, rejection, and internalised homophobia or transphobia. The guilt and fear stemming from their experiences, compounded by religious beliefs, create a heavy emotional burden.” Mumba notes. “Anxiety levels also spike, especially regarding relationships and identity, as survivors constantly worry about how others perceive them. Additionally, many may develop PTSD if they face severe negative reactions from family upon coming out, leading to long-term trauma. Lastly, suicidal ideation and self-harm are serious risks for those who have endured such experiences.”

Amidst the pain and abuse, hope emerges through the efforts of organisations like PEMA Kenya. Established in 2008, PEMA is a membership-based organisation dedicated to bridging the gap between the general public and the gender and sexual minorities (GSM) community through advocacy and capacity building. Alfred Obuya, a gay man and one of PEMA’s beneficiaries moved from Western Kenya due to hostility.

“As the lastborn in a polygamous family, my family had suspicions about my sexuality. My father died when I was six months old and after my mother’s death, my family told me I wasn’t their child. I now realize they were trying to get rid of me after they started doubting my sexuality.” Confused and hurt, he left home at 18. “I initially stayed briefly with my aunt in Kakamega County before moving to Mombasa,” Obuya recalls.

He met a friend who introduced him to PEMA Kenya. Initially, he was skeptical about joining but decided to try. Through PEMA’s UTU Barazas, an initiative promoting dialogue and understanding around issues of sexual orientation and gender identity, he found support and community.

“Through PEMA, I’ve received valuable training on community living and handling stigma. A friend invited me to the UTU Baraza, where we shared stories, learned to identify and report violence, and discussed solutions to our challenges. I’ve gained the courage to remain calm in tough situations. I used to be very aggressive due to my past, but now I think before responding, allowing me to react in a more informed and understanding way.”

Later, he returned home to visit the only sister who had stood by him. During this visit, his brother questioned why he wasn’t married yet. Obuya, now 26 years old, recalls responding, “Marriage isn’t a must. I’m an adult, and that’s my personal choice. Don’t I have the right to make my own decisions?”

Not everyone is as empowered as Obuya is now. For many survivors, pursuing legal action against their abusers is incredibly challenging. In cases like Ali’s, it becomes even more complicated when the abusers are family members. Some survivors hesitate to sue because they’ve seen others try with little to no outcome. Others fear retaliation from the perpetrators, making them reluctant to seek justice. Advocate Kioko acknowledges this as a valid concern and offers solutions to overcome it.

“There is a privacy and confidentiality policy. If they prefer anonymity, we can use pseudonyms and ensure no journalists are present. We’ll discuss their desired level of privacy, and if safety is a concern, we can collaborate with witness protection.” Kioko explains.

Ali is just one of many survivors who live with the repercussions of the abuse they endured, underscoring the need to end these harmful practices.

“I’m doing okay, but the past haunts me,” he reflects. “When you realise your parents are against you, it cuts deep. Not a day goes by without that pain; it stresses me out. I fell into depression after my marriage, and later, I was diagnosed with Type 1 diabetes, which only intensified the stress. This has affected my health and my ability to raise a family. It hasn’t been fair!”

Produced in partnership with the Thomson Reuters Foundation through the Hivos Free to be Me program.

Add comment